Information: The Forgotten Asset

[glossary_exclude]Over fifty centuries ago, a man received 29,086 measures of barley over 37 months. He documented this transaction on a clay tablet, then he signed it, “Kushim.” Kushim is the first person in history whose name we know according to Yuval Noah Harari’s book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Kushim was neither a king nor a prophet nor a warrior nor a poet. Instead, he was an accountant or so it would seem. The tablet found in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) has various dots, boxes, sheaves of grain pressed into it with a wedge-shaped stylus. It appears to record a business deal. (1)

Kings, prophets, and even deities come and go. But keeping track of your grain, your workforce (slaves back then), and your gold has been a constant throughout civilization, and across civilizations.

Tens of thousands of other clay tablets found dating back even centuries earlier record payments in cattle, shipments of cattle for fattening, gifts of cattle to the temple as an offering, years of feeding barley to donkeys, and even how the government taxed its people. (2)

Known recordkeeping goes back even further to simple tokens and clay balls with various shapes representing different kinds of inventory found in Jericho near the West bank of the Jordan River some 11,000 years ago. It took about another 6,000 years for the abacus to first appear in Sumeria even before the modern numerical system. (3) Some ten centuries later, papyrus became popular for tax receipts, court documentation, and other recordkeeping.

In ancient Egypt, the accountant was called the “eyes and ears” of the king. (4) Unlike present-century banksters, who avoid punishments other than a slap on the wrist for their complicity in crashing an entire economy, royal auditors of ancient Egypt imposed severe, even capital, punishment for accounting irregularities. (5)

It wasn’t until another 2000 or so years had passed when not only the transactions themselves were recorded, but when transaction laws were codified. The Code of Hammurabi, created in Babylon around 1760 BCE, is a seven-and-a-half feet tall stele of volcanic basalt (i.e., bigger even than the US Tax Code!). The Code of Hammurabi had 282 laws chiseled into it with various levels of punishments, such as the infamous “an eye for an eye” over a thousand years before it later appeared in the Hebrew Bible. These laws deal with contracts, wages, liability, and household and family matters (including sexual behavior). (6)

Another 500 years later, we begin to see the first artificial, yet more highly exchangeable representations of value. Around 1100 BCE the Chinese started using miniature replicas of items cast in bronze to represent the transfer of ownership of the actual objects themselves. Over time, these replicas were abandoned in favor of more uniform circles—the first coins. And in another 500 or so years, Lydia’s King Alyattes minted the first official currency, in present-day Turkey. These coins were stamped with pictures of snakes, lions, owls, and roosters denoting their denomination. About the same time back in China, they were evolving to use paper money. Around the time Marco Polo visited China in 1200 AD, the emperor had become quite adept at managing the money supply. Instead of “In God We Trust” as is inscribed on American currency, his currency ominously cautioned, “All counterfeiters will be decapitated.” (7)

To find the next significant accounting innovation, we need to fast-forward nearly two thousand years through the Dark and Middle Ages. One of the greatest and least known significant characters of the Renaissance is a Venetian merchant and mathematician named Luca Pacioli. Disgusted by the state of mathematics in Italy, Pacioli, two years after Columbus “discovered” the New World, published the book, Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita (The Collected Knowledge of Arithmetic, Geometry, Proportion, and Proportionality). Buried in this tome is one section that made Pacioli famous and is celebrated by accountants today, Particularis de Computis et Scripturis, a treatise on accounting, in which he becomes the first person to detail double-entry accounting, known then as “the Venetian Method,” which had been used for the past couple hundred years. (8) After his accounting manual opens with a listing of the three key components needed by anyone wishing to carry on an enterprise (capital, a good accountant, proper internal control), he wrote, “quanto alor debito e anche credito” or “whenever there is a debit entry there is also a credit entry.” This 1494 publication remains the basis of modern-day accounting: a company’s credits must balance its debits. (9)

Some 300 years later, a potter in the north of England built the world’s first industrialized pottery factory. Josiah Wedgwood (incidentally, Charles Darwin’s grandfather) capitalized on the demand for luxury goods by a new upwardly mobile class, enabling him to charge exorbitantly for his products. But during the recession of 1772, as demand for his pottery relaxed, Wedgwood turned to his accounting books to solve the problem of reduced cash flow and increased inventory. From these double-entry accounting records, he was able to calculate the cost of “every expense of Vase making” to determine whether to cut prices or production, therein inventing what we call today cost accounting. In turn, he learned how to distinguish between fixed and variable costs and how to uncover fraud within his company. Until this time, profit and loss had been merely generalized concepts. (10)

Speaking of fraud, it took another century for accountants to formalize the integration of factory production and commerce into a single set of books. Around the same time, the first accountancies were formed. A London railway and hotel accountant named William Welch Deloitte had gained a reputation for developing standards for these industries. At only 25 years old in 1845 he formed an accounting practice and was tapped to unravel the infamous frauds at the Great Northern Railway and Great Eastern Steamship Company.

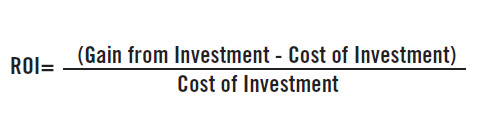

The next major accounting innovation comes another 60 years later. In 1914 a young salesman at DuPont named Donaldson Brown unwittingly created a simple formula for assessing and benchmarking business performance by combining investments, working capital, and earnings. The “DuPont Equation” is used today by every business in the world and is better known as Return on Investment. (11)

A couple of decades later, in response to The Great Depression, a committee chartered by the nascent Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) was tasked with standardizing financial statements. Until that time, both public and private companies could disclose what they wanted, however they wanted. This lack of consistency was blamed in part for investor confusion leading to the market crash. Part of these standards included homogenizing the set of recognized asset classes to be reported. Information, of course, was not one of these asset classes, because it wasn’t until some fifteen years later that the inklings of the information age emerged when the accounting firm Arthur Andersen computerized the payroll system for a General Electric plant. Only then was the idea hatched that information could be an item separable from its physical manifestation—the paper (e.g., book, magazine, ledger) it was printed upon.

INFORMATION IS STILL NOT CLASSIFIED AS AN ASSET

So, here we are today, some 60 years after the beginning of the Information Age, yet the namesake of this age, and the major asset driving today’s economy, information, is still not considered an accounting asset. Even though information meets the accounting criteria of one: information can be owned and controlled, it is exchangeable for cash, and it generates economic value. Ironically, while information is at the crux of accounting and has been for millennia, even in today’s information economy, it is not something accounted for itself. Regardless of the accounting profession’s antiquated notions of what is and isn’t an asset, it’s imperative in today’s economy for organizations to treat information as an actual enterprise asset—including accounting for it. At least internally, for now.

[/glossary_exclude]Regardless of the accounting profession’s antiquated notions of what is and isn’t an asset, it’s imperative in today’s economy for organizations to treat information as an actual enterprise asset—including accounting for it.

recent posts

You may already have a formal Data Governance program in […]