Electronic Privacy and US Law

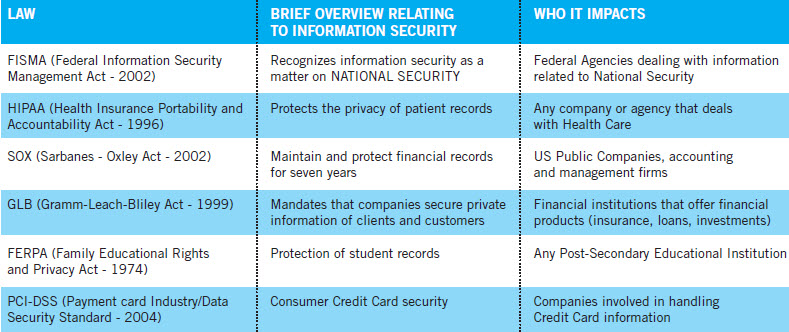

The U.S.’ patchwork system has been expanding since at least since 1986 with the passage of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), which bridged an existing gap between electronic transfers and computer aided transfers using the Internet. Before the ECPA, US federal law had been developing since 1970 to protect electronic transfers that used traditional telephony. (3) The result is a complicated mess of Congressional acts that contain bits and pieces of relevant law implemented piece-meal as specific actions were deemed to be violators of privacy. This explains in part why lawyers and compliance officers solicit substantial consultation fees.

Other U.S. Acts that have electronic privacy components include:

• The Federal Trade Commission Act

• The Financial Services Modernization Act

• The Fair Credit Reporting Act

• The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act

• Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

This hodgepodge system of overlapping laws arguably encourages hacking and necessitates a stronger focus on cybersecurity for organizations trying to secure sensitive and personally identifiable information (PII).

Ultimately, this meant someone needed to define elements of electronic information that should be private and protected. Although it has always been assumed that personal records such as credit card numbers and Social Security numbers must be kept private on the Internet, the federal government has been slow to define PII. In 2008, the United States Federal government defined PII in the broadest terms possible: any information about an individual maintained by an agency, including (a) any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual‘s identity, such as name, social security number, date and place of birth, mother‘s maiden name, or biometric records; and (b) any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.

This definition focuses on privacy after the fact, meaning a person must do something in cyberspace before protection of PII becomes an issue. This definition is problematic, in part because it is reactive, but also because the EU and most of the rest of the developed world view electronic privacy as a human right. (4) In the US electronic privacy is “action-focused”. The EU defines electronic privacy as “person-focused.”

The EU approaches PII from the “person” perspective, or what actions a person could potentially undergo that would trigger PII protection. This aligns with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights: “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life.” (5) GDPR Article 4 defines the person first: an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location number, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

Actions an individual takes while in the digital realm, call for a broad definition of PII. (6) Yet from the EU’s perspective PII is a catch-all approach that might give some American business headaches as they think about selling products to EU customers. The scope of person-centered privacy is illustrated in Figure 2.

Given the EU’s approach to protecting PII, American businesses will likely have issues understanding the interplay between four specific rights GDPR expressly gives EU’s citizens. These rights are:

1) the Right to access personal data;

2) the Right to be forgotten;

3) the Right to erasure;

4) and the Right to data portability.

American businesses have great challenges ahead as U.S. consumers are awakening to the daily incursions into their privacy. A recent USA Today poll found that Americans are now more concerned about personal privacy than either healthcare or the economy.[/glossary_exclude]

recent posts

You may already have a formal Data Governance program in […]